Making Storytelling Easier

Whether you like story templates or don’t, this is my last thought on what I think is their first problem: they give students the illusion that they will make story-crafting easy, or fast, or less messy. On paper, the recipe looks simple. In the kitchen, things get complicated. Even for seasoned professionals, suffering is part of the process. Some of the best admit it.

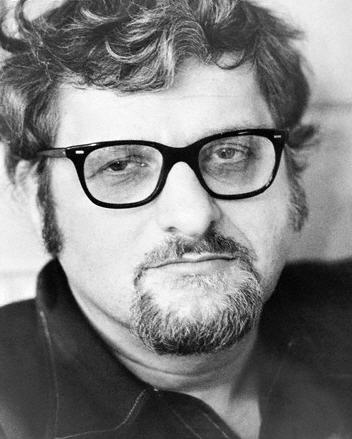

Three-Time Oscar Winning Screenwriter

Paddy Chayefsky, the revered television and screenwriter of the 20th century, warned about times when a writer “cannot pull himself out of a fruitless line of thought for hours, even days, sometimes never, and the script has to be abandoned in the middle.”[1. Television Plays, by Paddy Chayefsky, 1955, pp. 86-87 of Printer’s Measure: A Construction. I’m posting Paddy’s paragraph-long quote here if you want to read more.] This is a pro, and he’s not alone. Joseph Heller said “Every writer I know has trouble writing,”[3. Peeking at Pillars by Steven R. Lundin (quotes on quotes on writing), 2012, p113.] and Gene Fowler said “Writing is easy; all you do is sit staring at the blank sheet of paper until the drops of blood form on your forehead.”[4. The best I can do in tracking down Gene Fowler’s quote is 1980 August 10, New York Times, BOOK ENDS: Writers on Writing by Randolph Hogan, Page BR9, New York. Copied from quoteinvestigator.com—writing-bleed] This comes from accomplished legends. One wonders why they didn’t just use templates.

Every masterpiece looks easy to those who don’t know how it’s done, and every profession has hidden challenges. We shouldn’t be surprised. Good work usually takes a good deal of struggle.

Fortunately, the opposite happens as well. One team of Simpsons writers recalled working on The Telltale Head, saying it was “a lot of fun, and it went very fast, like three days…. an act a day.”[5. Al Jean, Mike Reiss, Sam Simon and Matt Groening on the DVD commentary track. One said that they spent a disproportionate amount of time naming the three bad kid characters, and finally decided on Jimbo, after their producer James Brooks.] That kind of near-spontaneous creative output happens when we are in the game, carried along by surges of energy, or just lucky.

But we cannot predict it. To use Stephen King’s analogy about excavating bones, some come up with an easy pull, and some take days of extraction.[2. This is not unique to writers. Frank Frazetta, one of the most notorious illustrators for “banging out another masterpiece” the night before it was due as if it were easy, acknowledged that “Most come easy, some come hard”. — Rough Work: Concept Art, Doodles and Sketchbook Drawings, by Frank Frazetta, Cathy Fenner, Arnie Fenner, 2007, Spectrum Fantastic Art] Also, some bones break. And some turn out to be rocks.

Creativity is easy when it just happens. But when it doesn’t… when you are at a loss to bring a boring character to life or make the dialogue sound less fake… when you doubt your measly defense of your symbolic-but-disappointing ending… when you face a million dizzying options the night before your ideas are due and realize that a stupid choice could embarrass you in front of your peers, brand you as a failure, and destroy your reputation or even your ability to stay alive in the entertainment industry… you will be tempted toward the promise of easy success by summoning the Plot Genie.

Creativity is easy when it just happens. But when it doesn’t… when you are at a loss to bring a boring character to life or make the dialogue sound less fake… when you doubt your measly defense of your symbolic-but-disappointing ending… when you face a million dizzying options the night before your ideas are due and realize that a stupid choice could embarrass you in front of your peers, brand you as a failure, and destroy your reputation or even your ability to stay alive in the entertainment industry… you will be tempted toward the promise of easy success by summoning the Plot Genie.

If that works, let me know.

If not, consider that the way you learn to tell stories is the way you learn any complex art form, from picture-making to cooking. You learn about process: how do professionals do their jobs? You learn about the basic skills. You spend a few years practicing basic skills. You apply them first to small projects, then to larger ones until you master them. In storytelling, these basic skills include creating character empathy, developing conflicts, crises, and tension, arranging reversals, and satisfying audience expectation. You learn about subtext. You learn how contrast, metaphor, and irony have special meaning to a storyteller.

These are not formulas. They are labels for story elements and principles that are as old as anyone knows. They apply to all kinds of stories from jokes to novels, from cartoons to crime thrillers. Each of them is worth a week of lessons. They make a story worth telling because they satisfy basic hungers that draw us to stories. They are craft.

When we get easy with craft, we can run without stopping to analyze steps. We can cook up a storm without consulting books. we can channel rushes of inspiration the way Arthur Miller did, “carrying an iron rod during a lightning storm.”[7. It’s one of the last questions in this interview from The Paris Review by Christopher Bigby.]

But it takes preparation. It is the cook who has spent time in the kitchen whom you trust to improvise a meal. It is the storyteller who knows how to weave a yarn who can weave it in flow.

But it takes preparation. It is the cook who has spent time in the kitchen whom you trust to improvise a meal. It is the storyteller who knows how to weave a yarn who can weave it in flow.

Mastery. It’s different from quick-fixes. George Leonard teaches it in his book Mastery. He gently guides you away from its enemies, nurtures you toward long-term skill, and encourages you to enjoy the work as you grow. Robert McKee teaches the same lesson in his book Story, though less gently. He lays down the law, confronts what a wuss you are for thinking it should be easy, and shames you for whining about having to bleed a little for your audience.

Mastery. It’s different from quick-fixes. George Leonard teaches it in his book Mastery. He gently guides you away from its enemies, nurtures you toward long-term skill, and encourages you to enjoy the work as you grow. Robert McKee teaches the same lesson in his book Story, though less gently. He lays down the law, confronts what a wuss you are for thinking it should be easy, and shames you for whining about having to bleed a little for your audience.

McKee is the renowned teacher of story craft. He is the most controversial, and the least. In a coming entry I’ll tell you a bit about what he offers, and doesn’t, and how it can help you master storytelling.