Templates & Formulas

Templates & Formulas

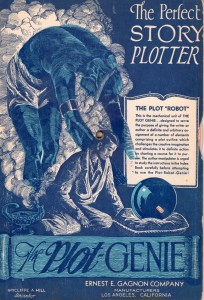

Story templates are not new to the 21st century. In the 1930’s, The Plot Genie helped writers assemble a plot with a spinning wheel and lists of situations.[1. It is back in print, and if you use it and like it, please let me know.] I tried it decades ago, but couldn’t bring myself to care about my story because it wasn’t mine. It felt like putting a frozen dinner in the microwave and claiming I cooked it.

There are many templates, matrixes, grids, and formulas. The classic three-part “Setup, Conflict & Resolution” is so universal and general that it’s hardly a template, but “22 building blocks” is definitely a template.

Some people love templates. They feel comforted having the sections laid out in advance. Some people hate templates. They feel bound by formula as if in a straitjacket. But straitjackets are not necessarily bad. They can keep a person from doing crazy things. A well-designed straitjacket may even improve posture.

Formulas are not necessarily bad. Formulas are familiar. They can be good. Any meal from a recipe is a formula. So is a strawberry. So is a baby.

In fact, formulas can enhance creativity. They give a creator something to press against. Television writers[2. The Simpsons first three seasons include impeccably crafted stories. As far as I know, the writers didn’t offer a single innovation in form. They relied on story devices as old as The Dick Van Dyke Show and the Book of Esther. All they offered was the best writing that TV had seen so far. This may have been decades ago, but when it happened, it was now, and though it was old formula, it was fresh story.] have proven this since before I was born. TV shows had to keep an audience through commercials or they died quickly. That’s why hooks and pointers, crises and game-changing reversals evolved in television writing to happen at prescribed moments. Some writers take these limitations as a challenge to test their inventiveness. When they succeed, they’ve mastered the formula.

But formulas have a few problems. First, they are not enough. Recipes dictate structure but cooks provide ingredients. The nouns and verbs in a story, the characters, events, transportation devices, and tactics of battle between nations and families – come from the storyteller. A kitchen of cookbooks won’t feed you.

And the critics have a point. Formula can harm a good story. Imposing a prescribed structure onto something yet to be discovered is like tailoring clothes for an unknown person. And at some point, formula becomes counterproductive. If 22 steps are better than three, are 40 better than 22? How about 100? Will that refine a story or bind it into tighter clothes?

Stephen King has an entirely different approach. He says “stories … pretty much make themselves”[3. Stephen King On Writing, 2000, p. 163] and likens writing to excavating. As a writer, you dig up fossils. You don’t invent the animal so much as discover it. The bones may belong to more than one animal but you can’t know until you try to assemble them.

This attitude of exploring has advantages over forcing. For one thing, it suggests how to use story templates. They are anatomical charts. As we study them, we heighten our awareness of structure and assess their relevance to the fossil we are digging. It may prove to be a different animal than we expected.[4. Stanley Kubrick originally intended for Dr Strangelove to be a serious apocalyptic movie called Two Hours to Doom. As it progressed, he began to realize from the absurdity of the events that he was digging up, not a drama, but a black comedy. – Dr Strangelove BluRay: extra features] Knowing the charts can help us identify and assemble what we dig up. But we should learn to use them wisely.

In the next entry, I’ll explain what I think is the biggest pitfall of story templates for students, and how professionals rely on something that is at once riskier and more dependable…